My roots grow in the jackpine roots! I am born here. I branch here. The government got all this country, how big it is. He don’t pay five cents – still he got it all! Nobody kicks me out! No sir!

Elder Kitty Smith’s testimony to former commissioner of the Yukon Territory

(in Cruikshank 1998:16)

The growing interest in the study of “unusual” or “exotic” languages and their dialects in nineteenth-century Europe coincided with colonial expansion and the creation of nation-states. Western ideologies link one culture with one language, maintaining that culture of one community is best studied through the use of their language. Political significance of this one culture, one language ideology was further advanced with the idea of “one nation, one language” – where a unified nation was a nation with one common language and the presence of multiplicity of languages and language varieties was seen as a obstacle and threat to this unity (Gal and Irvine 1995).

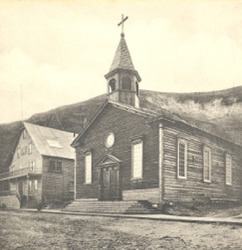

The erosion of languages throughout northern Canada – as in other parts of the country – is historically linked to the evolution of Euro-Canadian interests in the north. While these interests were primarily economic at first, attempts to replace Indigenous languages with standard colonial ones – namely English – were enacted through patterns of settlement of southern labourers, through evolving political relations with state agents and representatives such as the RCMP, as well as through conversion to dominant, state-sanctioned religious institutions and residential schools. In this respect, language loss is a product of broader efforts to systematically eliminate Indigenous and other minority languages. Even today, when there exists an increased awareness of the need to preserve and promote the use of traditional languages, English remains the first language of business, politics, and education, all of which amounts to a dominant presence of English throughout northern regions.

Language is a dialect with an army and a navy, the well-known saying goes, but what does it actually mean? What this saying is getting at is the fact that linguistic differentiation is embedded in the politics of a region and also in its observers.

“Together Today for Our Children Tomorrow” - Report - section on language education

together_today_for_our_children_tomorrow

Cruikshank, Julie (2005) Do Glaciers Listen?: Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Interactions. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Hall, Rebecca. (2013). “Diamond Mining in Canada’s Northwest Territories: A Colonial Continuity,” Antipode Vol. 45.2: 376-393.

Hoogeveen, Free entry principle and diamond mining?

Kulchyski, Peter and Frank Tester. Kiumajut (Talking Back). Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007.

Meek, Barbra, A. (2011) Failing American Indian Languages. American Indian Culture and Research Journal 35(2): 43-60.

Nadasdy, P. (2003). Hunters and Bureaucrats. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Perley, Bernard, C. (2011). Language as an Integrated Cultural Resource. In Companion to Cultural Resource Management. Thomas F. King, ed. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Philips, Lisa (2011). Unexpected Languages: Multilingualism and Contact in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century North America. American Indian Culture and Research Journal 35(2):19-41.

Tester, Frank and Peter Kulchyski. (1994), Tammarniit (Mistakes). Vancouver: UBC Press.